The ATT ambush

When Apple used the App Store to break online advertising

I've previously written about Apple's introduction of Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) and the cat-and-mouse game that followed between Webkit and online advertisers. This post picks up where that one left off, but with a brief recap.

In the months following the announcement of ITP 1.0, in June 2017, the Ad Tech community got to work looking for ways to bypass the restriction of third-party cookies in Safari. And whenever a particular workaround caught steam, Webkit released a new version of ITP to deal with it.

That is how things played out for a variety of tracking methods, old and new,

including link decoration, bounce tracking, the modification of

document.referrer, and on.

As I covered before, link decoration became notably popular, even getting

adopted by advertising giants including Facebook and Google. Sometime in late

2018, every link out of facebook.com was getting an extra ?fbclid parameter

appended to it, which could then be used by pixels in the destination websites

to identify the logged-in user.

Facebook chose to link-decorate not only ads but every outgoing link inside of

the apps and websites they owned. This included user-submitted URLs to websites

that weren't designed to handle the extra ?fbclid parameter and at times

failed to work because of it. (While it might be easy to sympathize with

advertisers' needs to preserve ad attribution in Safari despite the new

restrictions, Facebook's decision to link-decorate everything displays an

intention of restoring the cross-site tracking to the extent it existed before.)

Predictably, a crackdown ensued.

First in

April,

then in September

2019, the

Webkit team announced updates meant to deal with the link decoration

workarounds. In these announcement posts, Facebook was all but called by name.

The example scenarios referred to a website called social.example who

link-decorated using parameter ?clickID. By early 2020, following the release

of ITP 2.3, the vast majority of Apple users were running versions of the Safari

browser (on both macOS and iOS!) that made them impervious to cross-site

tracking.

And yet, three years after the introduction of ITP, there remained one place where Apple users were still being cross-tracked all around: right under Tim Cook's nose, inside the App Store.

An ITP for the App Store

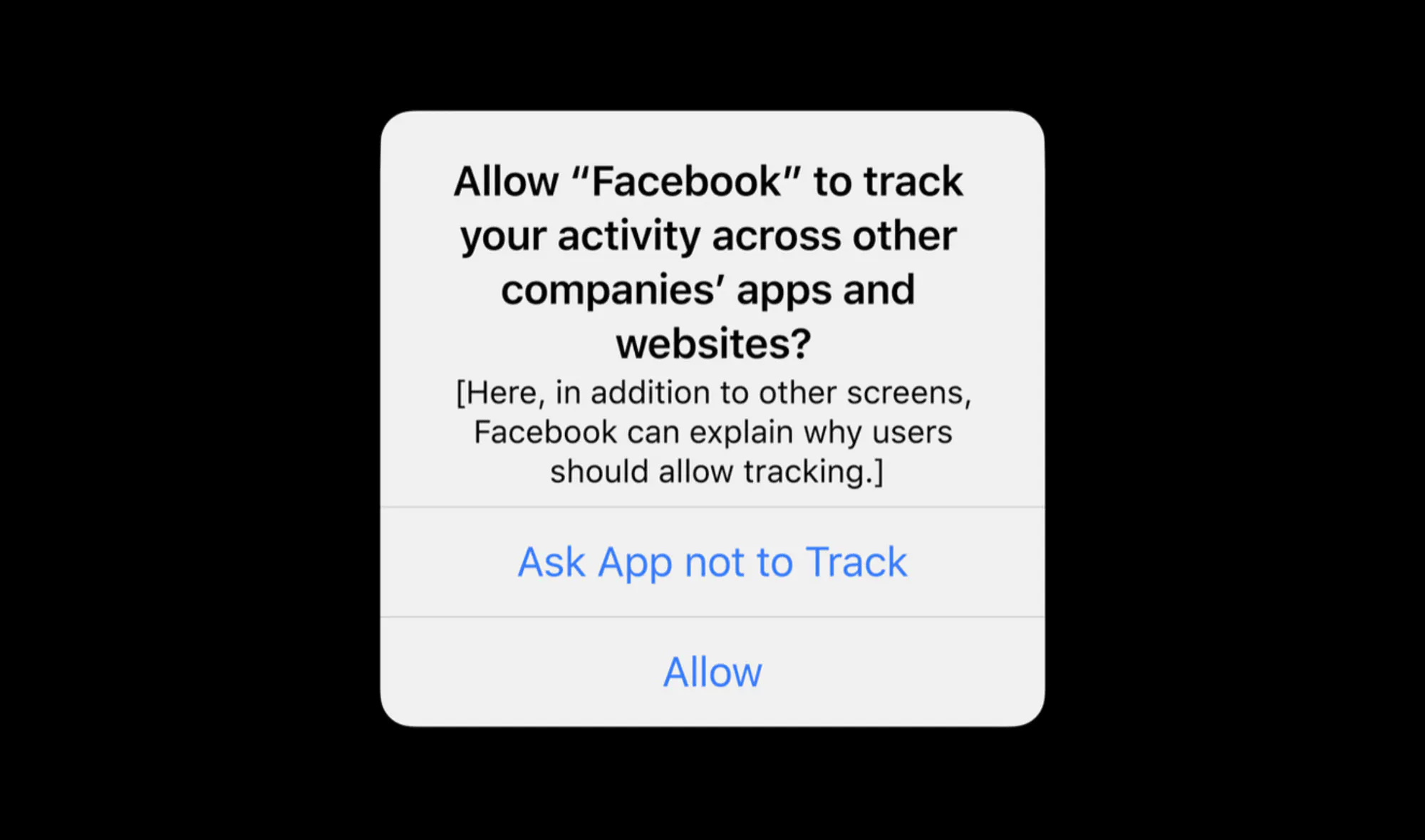

App Tracking Transparency, or ATT, is like ITP for apps. Few places explained it that way, perhaps out of fear of over-simplifying it, but this is more-or-less how Apple themselves introduced the feature during WWDC 2020.

Here's Katie Skinner during the keynote:

Katie Skinner introducing ATT during WWDC 2020

Next, let's talk about tracking. Safari's Intelligent Tracking Prevention has been really successful on the web. And this year, we want to help you with tracking in apps. We believe tracking should always be transparent and under your control. Moving forward, App Store policy will require apps to ask before tracking you across apps and websites owned by other companies.

The first stage of grief, as they say, is denial. While the news of ATT surely sent the Facebook high-command into crisis mode, evidence suggests that it took them months to realize the full extent of the damage it represented. To understand why, we must take a step back.

It came down to Apple's vague use of terms like "tracking".

The popular sentiment following WWDC was that ATT was all about deprecating iOS' Identifier for Advertisers feature, or IDFA. For several years, mobile advertisers had relied on the IDFA as the way to uniquely identify an iOS device across different apps. This gave them the ability to personalize mobile ad campaigns, attribute conversion events (ie. app downloads), and even retarget users based on anonymous activity.

The IDFA was, in short, like third-party cookies for apps. It enabled tracking between iPhone apps to exist. And, by late 2019, seeing what Apple had done with ITP, many experts agreed that the feature was likely on its way out. As Eric Seufert once put it, it had been "living on borrowed time".

Naive optimism

ATT would do to the IDFA what ITP had done to third-party cookies (ie. phase them out). This sums up how much of the public interpreted the new App Store policy.

Even at Facebook, executives took ATT to mean that developers would have to ask users for consent before reading their device identifier. Their first statement on ATT was published on August 26th, two months after WWDC, and it read:

First, we will not collect the identifier for advertisers (IDFA) on our own apps on iOS 14 devices. We believe this approach provides as much certainty and stability that we can provide our partners at this time. We may revisit this decision as Apple offers more guidance. ... We believe that industry consultation is critical for changes to platform policies, as these updates have a far-reaching impact on the developer ecosystem. [...] We look forward to continuing to engage with these industry groups to get this right for people and small businesses.

In sum, Facebook had decided to comply with ATT, not by showing the tracking prompts to users, but by dropping the use of IDFAs from their apps. Without the identifier, they surely expected to use other ways of distinguishing between Facebook users in third-party apps, just as they had used workarounds for cross-site tracking after ITP.

It was nevertheless a sacrificial move for the company. One immediate consequence of the decision to drop the IDFA was that the Audience Network product would be rendered useless inside of iOS, as another post went on to explain.

Facebook was, in effect, giving up one child to save the rest of the family. Because if losing Audience Network on iOS was bad, the alternative was unthinkable. Keeping the IDFA collection meant they would be forced to show users the new prompt, asking for consent to being tracked "across other companies' websites and apps". Facebook was desperate to avoid asking the question because they knew they wouldn't like the answer.

Big tech diplomacy

When I interned at Facebook, many years ago, I heard the rumor that an entire floor in the Menlo Park offices was reserved for marketers from other companies to come and work. Samsung, P&G, Coca-Cola, Apple... the biggest buyers of paid media would send their employees to our HQ, to spend millions of dollars while sitting next to dedicated support from Stanford engineers.

That was the rumor, in any case. But can you imagine how awkward this past year would have been for Apple contractors working inside a Facebook building, surrounded by media buyers and ad engineers whose jobs Apple had just made ten times harder? I can almost picture Sheryl Sandberg leaning in to shoo them away.

My point is that there is a lot more collaboration and coordination between tech giants than the public normally expects. For all the bravado and antagonism you see in the press, there can be a high level of rapport between teams working on similar issues inside two different companies. I doubt, for instance, that WWDC 20 was the first time that Dan Levy of the Facebook Ads org learned of Apple's intention to phase-out cross-app tracking.

This is what makes it all the more shocking, in retrospect, that Facebook's first advisory post on ATT could have gotten the situation so incredibly wrong.

The other shoe drops

Four months of silence followed the initial advisory on ATT, in what must have been a period of intense talks and diplomacy with Apple. When the Facebook team spoke again, in December 2020, their tone had changed.

Facebook is speaking up for small businesses. Apple’s new iOS 14 policy will have a harmful impact on many small businesses that are struggling to stay afloat and on the free internet that we all rely on more than ever.

- They’re creating a policy — enforced via iOS 14’s AppTrackingTransparency — that’s about profit, not privacy

- They’re hurting small businesses and publishers who are already struggling in a pandemic

- They’re not playing by their own rules.

- We disagree with Apple’s approach, yet we have no choice but to show their prompt

"We may revisit this decision"... indeed.

Sometime during the fall, Apple must have informed Facebook that they should take the word "tracking" in its broadest interpretation. Facebook would have to show the prompt even if they didn't plan on reading IDFA values at all. As companies with much cleaner records were about to learn, ATT applied to apps collecting almost any data that could be used to fingerprint users.

Then came Tim Cook's public response to Facebook: no tracking, of any sort, of nonconsenting Apple users.

Tim Cook on Twitter

Tim Cook's subtweet to Facebook

With one prompt, Apple had managed to push its two biggest rivals into a corner that had previously seemed not to exist.

Apple had never been the most likely gatekeeper for the internet, the ruler of what's allowed or not. That would be Google. With ITP, Apple tried to prevent cross-site tracking on the web, but had no mechanism to hold companies accountable for trying to bypass restrictions. Not the least because Safari makes up less than a fifth of the browser market. What could they do: block Safari users from accessing facebook.com?

As a result of ITP, Apple found itself in a yearslong pursuit of adversaries, with little to show for. Until, in 2020, Apple discovered — or stumbled upon — a way to bend competitors to its will, through the clever use of the App Store.

shocked, SHOCKED!, to find that Apple is holding the web back while pitching suspect privacy claims to bolster monopoly power to extract rents on software developers: https://t.co/r3xTlg1ZTq

— Alex Russell (@slightlylate) October 10, 2021

Take a moment to consider what Apple didn't do at WWDC 20:

They didn't announce the deprecation of the IDFA. Nor did they announce a change to their Terms of Service to ban cross-app tracking from iOS. Instead, with a simple prompt, they managed to position themselves as champions of user privacy; of users' right to choose. (Quite the performance coming from a $2T corporation!)

The choice of the prompt made it hard for the injured parties to protest (Who could be against users' right to choose?) while giving Apple the carte-blanche it had always wanted to hunt down advertisers beyond the borders of the App Store ecosystem.

This had been Facebook's worst nightmare following the announcement of ATT (one that had justified their haste in killing Audience Network): the fear that showing users the tracking prompt would end up killing both app-to-app and app-to-web tracking/attribution.

No room for maneuver

The day Facebook revised its public response to ATT was the day it launched a staunch campaign against Apple: "speaking up for small businesses".

Facebook's one-page

Facebook's one-pager on the WSJ. (@Dave Stangis)

The campaign was a total flop. It's hard not to ask what the hell they were thinking. Did they try a single focus group? But in a recent episode of the Mobile Dev Memo podcast, Eric Seufert made a great point about Facebook's limited room for maneuver in late 2020.

Part of the genius of [Apple's ATT move] is that it's such an exoteric field. If I was gonna go to war with a company that I perceive to be threatening one of my core lines of business, this would be the front I would want to attack them on.

I remember being surprised after seeing the WSJ ad for the first time. It seemed like an unlikely argument. Facebook had always had, to my knowledge, a terrible reputation among the SMB entrepreneurs whose companies relied on it for advertising. And I don't believe this has changed much over the past year.

To this day, the consensus online (Twitter, Reddit, DTC channels etc) is that Facebook doesn't care about any accounts dropping less than $250K/year on ads. The businesses they do care about are the big brands with a dedicated desk inside the Menlo Park offices.

And yet, what made the situation all the more ironic is that while the expensive Facebook campaign was quickly dismissed by the very community of small businesses that they pretended to care about, Facebook still had a point about Apple's laddering moves in privacy hurting small businesses most.

ATT did hurt small businesses and it's still hurting them.

Thanks to Michelle for helping me proofread, and to the folks at Mobile Dev Demo and Clearcode for the knowledge.